Asteroids - Nature's Death Stars

This Could Happen Next Year

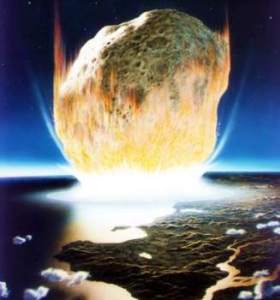

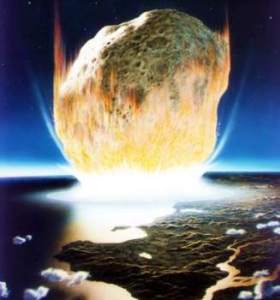

Image by Don Davis

An asteroid whose oblong orbit overlaps that of Earth and could, at some remote date, hit the planet with devastating consequences, was spotted January 10 by a telescope on the Hawaiian island of Maui, NASA astronomers revealed this week. The detection is just the latest success of a project called NEAT, for Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking program leaders said.Since going into action in late 1995 from Mount Haleakala on Maui, the fully automated system has added more than 4,500 small asteroids and comets to the list of known objects in the solar system. It has found more than 700 asteroids just since the start of the year. And including the latest one, some 14 of the new-found objects are in the fearsome "near-Earth" category.

"These have orbits that are so similar to Earth's that they are in a position to pose a hazard. There is danger lurking out there," said planetary astronomer and geologist Eleanor Helin, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

The newly discovered asteroid, dubbed 1997 AC11, is only the 24th asteroid known to have an orbit that lies mostly inside that of the Earth. The first of this kind, known as Aten asteroids, was found in 1976 by Helin, who is now the principal scientist for the NEAT project. She named the first one Aten after the early Egyptian religious word for "sun."

"As we continue to observe [the new object] in coming months, we will be able to characterize its orbital path with more precision. With more precise data, we will be able to examine its potential for collision with Earth at some time in the future," Helin said.

Although its exact orbit has yet to be determined, it is already clear that its closest approach to the sun brings it within the orbit of the planet Venus, making it also possible that gravitational perturbations of its path could someday send it into that planet.

Aten asteroids are not the only ones that could strike Earth. Another set, the Apollo objects, also have oblong orbits that cross within the Earth's distance from the sun. Apollos have slightly larger orbits with an average distance from the Sun greater than Earth's.

The recent finds bring the number of known Earth-crossing asteroids to about 200. Planetary scientists estimate that this is probably about 10 percent of all that exist. "We need to keep looking, to inventory them and see if there is something there that is a danger to Earth now," Helin said.

Although it may be hundreds of thousands of years between impacts on Earth by asteroids or comets, even a relatively small body a few hundred yards across could wipe out an area of thousands of square miles, and large asteroids or comets a mile or more across could threaten human civilization.

The most common asteroids, including the bulk of those detected by the new program, pose no danger to Earth because they are in the main asteroid belt between the orbits and Mars and Jupiter, the fourth and fifth planets from the sun.

The scientists estimate that AC11 is a chunk of rock about 600 feet across. It goes around the sun every 9.5 months. Although its average distance from the sun is less than Earth's, its elliptical path brings it to the same distance as Earth from the sun as often as as four times a year. But its orbit is tilted at a 31 degree angle to the plane of the Earth's orbit, the largest such tilt of any Aten object found so far. The angle of its orbit means that, at present, it cannot actually hit the Earth. But relatively minor gravitational interactions with Earth or Venus, or both, could change its tilt and bring it into a collision course.

The main instrument for the NEAT program is a 36-inch telescope at a U.S. Air Force facility on Mount Haleakala. The telescope is old, put there by the Air Force to track man-made satellites. But the NEAT project outfitted it with an extremely sensitive new detector, called a charge-coupled device, mounted at its focus. The telescope's measurements are automatically sent to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, where Helin and three colleagues, Steve Pravdo, David Rabinowitz and Ken Lawrence, analyze them.